This blog has touched on the debate over the date of Easter in the past, but the truth is that the early Church went through different phases before settling on the date of Easter.

Because the Last Supper was a seder, commemorating Passover, early celebrations of Easter coincided with that date. Passover took place on the 14th of the month. The early Church historian Eusebius tells us that the dioceses of Asia at the time of Pope Victor (pope from 189-199) celebrated Easter on the 14th day of the moon, regardless of the day of the week on which it fell.

This bothered some ecclesiastics and Christian scholars. Synods were held (Eusebius says) that agreed and decreed that the Easter celebration should be held on the Lord's Day, a Sunday. Some, however, refused to give up the tradition of celebrating on the 14th. They were called Quartodecimans [fourteenth-ers]. St. Polycarp (69-155), for example, came to Rome to discuss his preference for the date that he believed had been established by St. John the Apostle; he refused the command of Pope Anicetus (pope c.153-168) to change to Sunday.

Quartodecimans were tolerated for awhile, by popes like Anicetus at least. Pope Victor excommunicated the Asiatic dioceses, an action that got him criticism for unnecessary harshness from St. Irenæus.

Agreeing that Easter should be celebrated on a Sunday did not settle any debate; which Sunday was crucial. The Council of Nicaea (already mentioned several times in DM) tackled this issue. Syrian Christians always celebrated Easter on the Sunday following the 14th of the month, but other Christian dioceses calculated the date in their own ways. Antioch, for instance, based their date on the local Jewish observances, but had let slide a guideline that the 14th should be the month after the vernal equinox. Alexandria, however, demanded Easter Sunday be after the equinox—March 21st at the time.

Most native English speakers, if they know about the controversy of the Easter date debate, have heard of the Synod of Whitby in 664, at which Roman Christianity and Celtic/Irish Christianity fought it out over topics such as the date of Easter and the style of monastic tonsures. Whitby established for the English-speaking world that Easter would fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon (the 14th of the lunar month) after the vernal equinox. If the full moon is a Sunday, Easter takes place on the following Sunday. Easter can be as early as March 22 or as late as April 25.

The Eastern Orthodox Church calculates differently. They had been using March 21st as their starting point, but followed a guideline that prevented Easter from ever falling on or preceding the same day as Passover. Orthodox Easter can fall between April 5 and May 8. In the 21st century, the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches tried to reconcile their different dates using more recent astronomical data for their calculations. They still calculate in different ways, but there is greater chance that the dates will coincide, such as in 2001 when April 15th was Easter for both Churches.

There. That was easy.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Anti-kings? Really?

Rudolph of Swabia was referred to as an anti-king after he was defeated by Henry IV in 1080. Anti-popes are a common concept in history, but were there enough anti-kings to justify a label? Can't we just call him a usurper?

There were actually quite a few anti-kings in the Middle Ages. One of the earliest was Duke Arnulf "The Bad" of Bavaria, who spent 919-921 claiming he was the alternative to King Henry "The Fowler" who was the first king of the Ottonian dynasty in Germany. After Henry defeated Arnulf in battle, he allowed Arnulf to keep the title of Duke of Bavaria so long as he renounced forever his claim to the German throne. Arnulf wised up, and did not create any more trouble, dying peacefully in 937.

Rudolf of Swabia was an anti-king who has already been referenced when discussing Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and his conflict with Pope Gregory VII. When Henry was out of favor, German aristocrats decided to elect an alternate, Rudolf, who lasted from 1077-1080. After he died in battle, Hermann of Luxembourg (also called "of Salm") took a chance. He lasted longer than Rudolf, from 1081-1088, but had to flee to Denmark in 1085. He returned in an alliance with Duke Welf of Bavaria, Rudolph's successor, but soon tired of the constant struggle (and being a pawn of the pope and German lords) and retired to his home. He was not heard of after 1088; we assume that was the year of Hermann's death.

The Germans either had a difficult time accepting their anointed rulers, or they just liked creating conflict. Several Holy Roman Emperors had to deal with anti-king challenges, right up until the mid-14th century!

There were actually quite a few anti-kings in the Middle Ages. One of the earliest was Duke Arnulf "The Bad" of Bavaria, who spent 919-921 claiming he was the alternative to King Henry "The Fowler" who was the first king of the Ottonian dynasty in Germany. After Henry defeated Arnulf in battle, he allowed Arnulf to keep the title of Duke of Bavaria so long as he renounced forever his claim to the German throne. Arnulf wised up, and did not create any more trouble, dying peacefully in 937.

Rudolf of Swabia was an anti-king who has already been referenced when discussing Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and his conflict with Pope Gregory VII. When Henry was out of favor, German aristocrats decided to elect an alternate, Rudolf, who lasted from 1077-1080. After he died in battle, Hermann of Luxembourg (also called "of Salm") took a chance. He lasted longer than Rudolf, from 1081-1088, but had to flee to Denmark in 1085. He returned in an alliance with Duke Welf of Bavaria, Rudolph's successor, but soon tired of the constant struggle (and being a pawn of the pope and German lords) and retired to his home. He was not heard of after 1088; we assume that was the year of Hermann's death.

The Germans either had a difficult time accepting their anointed rulers, or they just liked creating conflict. Several Holy Roman Emperors had to deal with anti-king challenges, right up until the mid-14th century!

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Canon Law and Muslims

Today picks up from the previous post.

Although canon law did not apply to non-Christian populations, that attitude changed when Europe came into greater contact with Muslims. The reason is explained by James Brundage:

In the 13th century, Pope Innocent IV (c.1195-1254; pope from 1243 until his death) declared that ownership of property was a human right, as part of the natural law established by God. He also declared, however, that although non-Christians may not be part of Christ's church, they were still part of Christ's flock, and therefore they should fall under the rule of Christ's vicar on Earth. (Innocent even sent a message to Güyük Khan, "Emperor of the Tartars" (c.1206-1248), to tell the Mongol ruler to convert to Christianity and stop fighting Europeans. The response from the Khan was that European rulers should submit to his rule.)

This view of the popes prevailed, reaching a peak in 1302 with Boniface VIII's papal bull, Unam Sanctam. For the next several centuries, Christian rulers had the license they needed to attack non-Christians and take their lands.

Although canon law did not apply to non-Christian populations, that attitude changed when Europe came into greater contact with Muslims. The reason is explained by James Brundage:

European Jewry had furnished the model upon which early canonists had formed their views about the legal relationship between non-Christians and canon law. Jewish populations, however, tended to be relatively small, stable (save when one ruler or another decided to expel them from his territories), and peaceful. They certainly posed no military threat to Christian rulers and only an occasional fanatic could seriously maintain that they menaced the Christian religious establishment.This interaction with the Muslim world caused canonists to re-examine the self-imposed limits of canon law and its application to non-Christians, especially when it came to whether it was proper for Christians to conquer and take Muslim territory. This may seem an odd concern to the modern reader, but remember that this was a time when ownership of property was not open to everyone. If Muslims fell into a category that was not allowed property—such as slaves or minors—then taking their lands was not an issue.

Muslims in the Mediterranean basin and pagans along Latin Christendom's eastern frontiers, however, were an altogether different matter. Many Christians considered them a serious threat to Christianity's goal of converting the world... . [Medieval Canon Law, p.163]

In the 13th century, Pope Innocent IV (c.1195-1254; pope from 1243 until his death) declared that ownership of property was a human right, as part of the natural law established by God. He also declared, however, that although non-Christians may not be part of Christ's church, they were still part of Christ's flock, and therefore they should fall under the rule of Christ's vicar on Earth. (Innocent even sent a message to Güyük Khan, "Emperor of the Tartars" (c.1206-1248), to tell the Mongol ruler to convert to Christianity and stop fighting Europeans. The response from the Khan was that European rulers should submit to his rule.)

This view of the popes prevailed, reaching a peak in 1302 with Boniface VIII's papal bull, Unam Sanctam. For the next several centuries, Christian rulers had the license they needed to attack non-Christians and take their lands.

Monday, March 25, 2013

The Limits of Canon Law

Since I've been looking into canon law lately (here and here), I thought I would share an interesting facet of Medieval era canon law: its self-imposed limits.

Although canon law borrowed a great deal from the jurists and civil law decisions of the Classical Era, it was grounded in church teachings. Therefore, from early jurists up until at least 1200, it was agreed that canon law did not apply to non-Christians. The rules of consanguinity adhered to by the church, for instance, forbidding the marriage of those who were related too closely by blood or legal ties (such as in-laws), did not apply to Jews or pagans. Nor was it legal for Jews or pagans to be made to tithe or be baptized against their will.

Of course, Christianity's goal was to spread the Gospel and convert the world, so it would be only a matter of time (it was thought) before canon law would apply to everyone. (The second post ever on DailyMedieval was about the Domus Conversorum, established in 1232 in England by Henry III to provide a home and daily stipend for Jews who wished to convert to Christianity, making their decision an easy one.)

Christianity ran into an unexpected obstacle to its ultimate goal, however, especially during the era of the Crusades. Whereas Jews were found in small and non-violent communities, Muslims were far more numerous and warlike; moreover, they were on their own mission to convert the world. This led—outside of the Crusades themselves—to border skirmishes where newly acquired Middle East Christian territories brushed up against Muslim lands.

The debate that followed will be looked at in the next post.

Although canon law borrowed a great deal from the jurists and civil law decisions of the Classical Era, it was grounded in church teachings. Therefore, from early jurists up until at least 1200, it was agreed that canon law did not apply to non-Christians. The rules of consanguinity adhered to by the church, for instance, forbidding the marriage of those who were related too closely by blood or legal ties (such as in-laws), did not apply to Jews or pagans. Nor was it legal for Jews or pagans to be made to tithe or be baptized against their will.

Of course, Christianity's goal was to spread the Gospel and convert the world, so it would be only a matter of time (it was thought) before canon law would apply to everyone. (The second post ever on DailyMedieval was about the Domus Conversorum, established in 1232 in England by Henry III to provide a home and daily stipend for Jews who wished to convert to Christianity, making their decision an easy one.)

Christianity ran into an unexpected obstacle to its ultimate goal, however, especially during the era of the Crusades. Whereas Jews were found in small and non-violent communities, Muslims were far more numerous and warlike; moreover, they were on their own mission to convert the world. This led—outside of the Crusades themselves—to border skirmishes where newly acquired Middle East Christian territories brushed up against Muslim lands.

The debate that followed will be looked at in the next post.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Ignorance of the Law

Ignorantia juris neminem excusat.

Ignorance of the law excuses no one.

Can ignorance of the law ever be an excuse?

The Middle Ages deliberated over this topic, ultimately drawing a distinction between two classes of people: those who had no excuse not to know the law, and those who did have an excuse for their ignorance. Canon law wanted to be strict and definitive, but it recognized that there were segments of society that could not be held completely responsible for their actions.

For whom was ignorance of the law an excuse? Actually, several groups were considered exempt from presumption of knowledge of the law:

...minors, madmen, soldiers, and, in most circumstances, women were commonly believed to lack the capacity (in the case of minors and the insane) or the opportunity (in the case of soldiers and women) to know and understand the law. [Medieval Canon Law, James Brundage, p.161]Much of medieval canon law came from Roman sources such as the Digestum Justiniani (the Digest of Justinian*) in 503. It assembled 50 books covering many topics by multiple jurists. In the Digestum, one classical jurist, Paul, draws a distinction between ignorance of the law and ignorance of fact. Although the legal system may not be able to presume that everyone knows the actual law, it must presume that everyone knows the fundamental factual difference between a good act and a bad act in their community. Otherwise, profession of one's ignorance becomes a universal excuse, and only those who are lawyers, judges, or politicians who actually make the laws would ever be able to be convicted.

Paul is also the jurist who created the basis for presumption of innocence when he wrote Ei incumbit probatio qui dicit, non qui negat. ("Proof is incumbent on him who asserts, not him who denies.") Although the accused could not avoid punishment by simply saying "I didn't know," at least he wasn't convicted based simply on another's say-so.**

*This was Emperor Justinian I (c.482-565), whose reign straddled the Classical and Medieval eras. The Digestum is not to be confused with the Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law), the much larger compendium (sometime called the Code of Justinian) that was assembled later in his reign, of which the Digestum was only a part.

**The phrase "Innocent until proven guilty" was coined by the English lawyer Sir William Garrow in the early 19th century.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

It's My Day Off...Again

There were 52 days of the year that no one should have to labor: Sundays. For the same reason that Sundays were taken off—everyone should be free to attend Mass—there were about 40 days in the calendar that were likewise taken off because they were saints feast days or other Holy Days (Annunciation, Christmas, et cetera).

Furthermore, there were sometimes local saints in the area—not found in the official liturgical calendar established by the 12th century—whose celebrations workers were obliged to observe. These could add 20-30 additional days off to a worker. All in all, a potential 120 days—one-third of the year—could be spent in "enforced leisure." That leisure often included feasts and dances in the community. In a world without the forms of entertainment we are used to now, communal feasts and other social gatherings could be the highlights of the season.

This was not necessarily a good thing for the laborer or the employer. If he were paid by the day, he lost a lot of wages on the days when he was not supposed to work. If an employer paid by the month or the quarter, there were several days when he got no work out of his employees although they were being paid!

[For more, see Medieval Canon Law by James A. Brundage, ©1995 by Longman Group Limited]

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

When Poets Collide?

Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377) was a classical composer and poet—in fact, one of the last poets who also composed music—and a part of the ars nova ["new technique"] movement which embraced polyphony. His name suggests that he was born in Machault, east of Rheims in France, but it is clear that he spent most of his life in Rheims. Unlike many non-royal figures of his age, his popularity has ensured that we possess a remarkable amount of biographical information about him.

As a young man, he was a secretary to the ing of Bohemia, John I. He was named a canon of Verdun, then Arras, then Rheims; by 1340 he had given up the other positions and was a canon of Rheims only. As a canon, attached to the cathedral in Rheims and living without private wealth, he could devote himself to composing poetry and music. In all, we have about 400 pieces in various forms.

He lost his first patron, King John of Bohemia, when John died at the Battle of Crécy in 1346 during the Hundred Years War. Machaut found support from John's daughter. When she died during the Black Death, he found support from her sons, Jean de Berry and CharlesV, Duke of Normandy.

In the next phase of the Hundred Years War, Geoffrey Chaucer (likely still a teenager at the time) was in the retinue of Prince Lionel as a valet. During the siege of Rheims in early 1360, Rheims rallied and captured the besiegers. Chaucer was taken prisoner. This would not have involved being thrown in dungeons and experiencing deprivation. The practice at the time was to capture as many high-ranking opponents as possible in order to gain money from ransoms. (Chaucer was ransomed for £16 in March.) The English would have likely experienced a mild form of "house arrest" which would have allowed them a certain amount of freedom. Chaucer would have had ample opportunity to visit Machaut.

Did he? We cannot be sure. Chaucer's poetry rarely offers attribution for his influences, but he was certainly intimately familiar with Machaut's work. Scholars have found numerous influences in Chaucer's writing. Chaucer scholar James I. Wimsatt has referred to "Guillaume de Machaut, who among fourteenth-century French poets exerted by far the most important influence on Chaucer."[link] Even long before he himself began writing, he was in a court that valued and supported the arts and poetry. Machaut was enormously popular in his own lifetime, and it seems inconceivable that Machaut would not have been sought out by several of the English who would have appreciated his reputation.

For a sample of his musical composition:

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Queenshithe

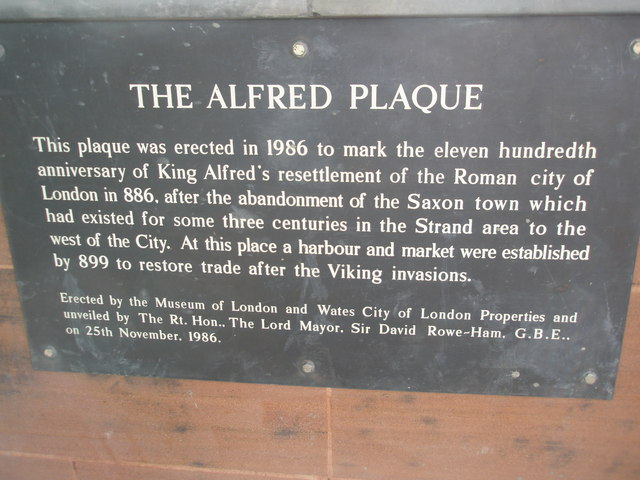

|

| Plaque in Queenhithe. |

The site is much older, however. As mentioned, it was no doubt established in Roman times—excavations have found remains of Roman baths in the area. When King Alfred the Great (849-899) "revived" the City of London around 886. Alfred made a gift of it to his brother-in-law Ethelred, and for a time it was called Ædereshyd, or "Ethelred's Dock."

It was an important landing place for ships bringing grain into the city. The nearby Bread Street has existed under that name at least as far back as the Agas Map. Also, Skinners Lane a block away attests to the import of furs, particularly rabbit skins.

It was designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1973, particularly as it is the only surviving site of a once-Saxon harbor. It is therefore protected from random alterations by construction. Its use as a port, however, has fallen off because of its position upriver from London Bridge, preventing large modern ships from reaching it.

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Sir Richard Stury

|

| King Edward and his knights counting their dead after the Battle of Crécy, Hundred Years War |

He was a chamber knight and a councilor to Edward III. He was also, like many of his fellow chamber knights, a lover of poetry. His will included an expensive copy of the Romance of the Rose.

He and Chaucer were well-acquainted. Their paths would have crossed frequently in London, and they were put together on an embassy in 1377 and a commission in 1390 to look into repairing the dikes and drains of the Thames.

Stury had a reputation for being a Lollard, a follower of the teachings of John Wycliffe. The popularity of this stance waxed and waned over the years, sometimes putting him in opposition to powerful forces in society.

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Banking Collapse of the 1340s

|

| Chapels of the Bardi & Peruzzi families in Santa Croce, Florence |

Florence was the headquarters for some powerful families in the Middle Ages who used their wealth and business acumen (and the stability of the Florentine gold florin) to create the first international banking corporations. Two of the biggest, run by the Bardi and Peruzzi families, collapsed in 1346 and 1343, respectively. The excuse for the collapse is often given as Edward III of England's default on loans he took to pay for expenses during the Hundred Years War. Estimates put Edward's debts at 900,000 florins to the Bardi and 600,000 to the Peruzzi--an enormous sum in any age.

More recent assessments of the situation, however, spread the blame. Edward's expenses were incurred earlier, and the two banks survived for some years afterward. Also, a third bank, the Acciaiuoli, failed in 1343 without having loaned any money to England. Various Florentine banks also loaned money to finance a war against Castracane of Lucca, and to put down a peasant revolt in Flanders. Also, an uprising in September 1343 in Florence created vast property damage that would have affected the banks (according to the 16th century historian Giovanni Villani).

It is impossible to understand every aspect of the collapse of the 1340s, especially since records such as we expect modern companies to maintain were not kept, and records that were kept did not necessarily survive until today. We do know that, in a world where nations did not maintain careful accounting practices, or have "social safety nets" established, it took very little to create widespread economic turmoil.

Saturday, February 2, 2013

Compurgators

The ultimate character witness.

Throughout several centuries and many countries, establishing your innocence or trustworthiness in a court of law could be done by the use of compurgators. The word comes from Latin com (with) + purgare (cleanse; hence the modern word "purge").

If you were accused of wrongdoing, you would gather compurgators to appear for you in court. Ideally, you would find 12 of the most respected members of the community who would be willing to stand there and say that they believe you when you say you are innocent. Mind you, if you were found standing over a dead body with a bloody knife in your hand, compurgators were not likely to save you. This worked well when you were accused of cheating on a debt or stealing a spoon and hard evidence did not exist against you...unless you had friends who were determined to protect you.

The opportunities for abuse of such a system were rampant.

Henry II, or instance, in 1164 made sure that compurgation would not be allowed in felonies; he did not like the fact that a cleric (priest) might literally get away with murder in an ecclesiastical court by merely being defrocked, while the royal courts would use capital punishment for capital crimes. The use of compurgation in any way as a defense in England was eliminated from the court system in 1833.

Throughout several centuries and many countries, establishing your innocence or trustworthiness in a court of law could be done by the use of compurgators. The word comes from Latin com (with) + purgare (cleanse; hence the modern word "purge").

If you were accused of wrongdoing, you would gather compurgators to appear for you in court. Ideally, you would find 12 of the most respected members of the community who would be willing to stand there and say that they believe you when you say you are innocent. Mind you, if you were found standing over a dead body with a bloody knife in your hand, compurgators were not likely to save you. This worked well when you were accused of cheating on a debt or stealing a spoon and hard evidence did not exist against you...unless you had friends who were determined to protect you.

The opportunities for abuse of such a system were rampant.

Henry II, or instance, in 1164 made sure that compurgation would not be allowed in felonies; he did not like the fact that a cleric (priest) might literally get away with murder in an ecclesiastical court by merely being defrocked, while the royal courts would use capital punishment for capital crimes. The use of compurgation in any way as a defense in England was eliminated from the court system in 1833.

Friday, February 1, 2013

Nicholas Oresme

Nicholas Oresme (c.1325-1382) likely came from humble beginnings; we assume this because he attended the College of Navarre, a royally funded and sponsored college for those who could not afford the University of Paris. He had his master of arts by 1342, and received his doctorate in 1356. He became known as an economist, philosopher, mathematician and physicist.

One of his published works was:

Livre du ciel et du monde

(The Book of Heaven and Earth)

In this work he discussed the arguments for and against the rotation of the Earth.

- He dismissed the notion that a rotating Earth would leave all the air behind, or cause a constant wind from east to west, pointing out that everything with the Earth would also rotate, including the air and water.

- He rejects as figures of speech any biblical passages that seem to support a fixed Earth or a moving sun. (Keep in mind even today we unanimously speak about the beauty of the sun setting when it's really the Earth rising!)

- He points out that it makes more sense for the Earth to move than for the (presumably more expansive and massive) heavenly spheres and Sun to move.

- He assures his readers that all the movements we see in the heavens could be accounted for by a rotating Earth.

- Then he assures the reader that everyone including himself thinks the heavens move around the earth, and after all he has no real evidence to the contrary!

Years later, Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) wrote his theories out in a way so similar to Oresme's that it is assumed he had access to Oresme's writing.

Thursday, January 31, 2013

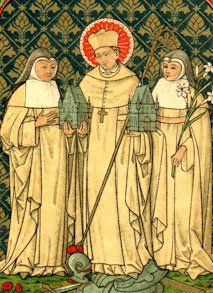

Monk Lord of the Manor

For some reason, a 12th century Norman knight named Jocelin did not want his son to follow in his footsteps. We do not know why, but a common modern assumption is that Jocelin's son, Gilbert of Sempringham (c.1089-1190), had some physical deformity that would have made his career as a knight and warrior untenable. Whatever the case, Jocelin sent his son to study theology at the University of Paris.

Gilbert came back to England in 1120 and, after being given the parishes of Sempringham and Tirington, joined the household of the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Bloet (who started as a clerk in the household of William the Conqueror and later became Chancellor).

He used his revenue from Tirington to aid the poor, and lived on the revenue from Sempringham. Robert Bloet's successor as Bishop of Lincoln ordained him a deacon, then as a priest after 1123, but when offered the archdeaconry of Lincoln he refused.

In 1130 his father died. Gilbert inherited his father's Lincolnshire manor and lands, and returned there. He did not, however, abandon the religious life. He now had the income to execute some grander plans. He decided to found his own monastic order.

The Gilbertines were originally composed of young men and women who had known and/or been taught by Gilbert in the parish school. It is the only monastic order founded in England. He used the Cistercians as his model, but when he appealed to the Cistercians themselves in later years for aid in maintaining and expanding the Gilbertines, he was rejected because of his inclusion of women.

Things turned sour for Gilbert in 1165, when he was imprisoned by King Henry II on the suspicion that he aided the fugitive Thomas Becket. He was eventually exonerated. Trouble found Gilbert again about 1180 when the lay brothers among the Gilbertines rose up because they were worked too hard (to enable the religious brothers to spend their days in prayer). The case was taken to Rome, but Pope Alexander III supported the 90-year-old Gilbert. Still, it is reported that living conditions for lay brothers improved afterward.

Gilbert, blind for the last few years of his life, resigned as head of the Gilbertines. He died in 1190 at the estimated age of 100+. His canonization did not take long: Pope Innocent III confirmed his sainthood in 1202, placing his Feast Day on 4 February, the day of his death, but it is now celebrated on 11 February.

Gilbert came back to England in 1120 and, after being given the parishes of Sempringham and Tirington, joined the household of the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Bloet (who started as a clerk in the household of William the Conqueror and later became Chancellor).

He used his revenue from Tirington to aid the poor, and lived on the revenue from Sempringham. Robert Bloet's successor as Bishop of Lincoln ordained him a deacon, then as a priest after 1123, but when offered the archdeaconry of Lincoln he refused.

In 1130 his father died. Gilbert inherited his father's Lincolnshire manor and lands, and returned there. He did not, however, abandon the religious life. He now had the income to execute some grander plans. He decided to found his own monastic order.

The Gilbertines were originally composed of young men and women who had known and/or been taught by Gilbert in the parish school. It is the only monastic order founded in England. He used the Cistercians as his model, but when he appealed to the Cistercians themselves in later years for aid in maintaining and expanding the Gilbertines, he was rejected because of his inclusion of women.

Things turned sour for Gilbert in 1165, when he was imprisoned by King Henry II on the suspicion that he aided the fugitive Thomas Becket. He was eventually exonerated. Trouble found Gilbert again about 1180 when the lay brothers among the Gilbertines rose up because they were worked too hard (to enable the religious brothers to spend their days in prayer). The case was taken to Rome, but Pope Alexander III supported the 90-year-old Gilbert. Still, it is reported that living conditions for lay brothers improved afterward.

Gilbert, blind for the last few years of his life, resigned as head of the Gilbertines. He died in 1190 at the estimated age of 100+. His canonization did not take long: Pope Innocent III confirmed his sainthood in 1202, placing his Feast Day on 4 February, the day of his death, but it is now celebrated on 11 February.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Asking Questions

|

| Image from Adelard's translation of Euclid's Elements of Geometry |

The 12th century saw an influx of more works, many of them Greek writings (preserved by Arabs) or Arab writings. The widening of philosophical and scientific horizons by this wave of knowledge caused many scholars to re-think what had been established.

Adelard of Bath (c.1080-c.1152) was an English philosopher who was in a position to translate into Latin for the first time many of the Greek and Arabic works becoming available to the West. After studying at Tours and teaching at Laon in France, he traveled for seven years through Italy, Sicily, Syria and Palestine. He translated Al-Kwarizmi's astronomical tables and Euclid's Elements of Geometry from Arabic, wrote works on the abacus and on his love of philosophy, and a book called Questiones Naturales (Natural Questions) in which he tackled, in dialogue form, 76 questions about the world. One of his themes is the choice of using reason rather than merely accepting authority.

For what should we call authority but a halter? Indeed, just as brute animals are led about by a halter wherever you please, and are not told where or why, but see the rope by which they are held and follow it alone, thus the authority of writers leads many of you, caught and bound by animal-like credulity, into danger. Whence some men, usurping the name of authority for themselves, have employed great license in writing, to such an extent that they do not hesitate to present the false as true to such animal-like men. [...] For they do not understand that reason has been given to each person so that he might discern the true from the false. [Questiones Naturales, VI]To be clear: Adelard's science is not ideal: his periodic table of elements contains only four substances, which are mixed in various proportions to create all materials. Some animals see better by day or night because of either white or dark humor in their eyes. We see because an extremely light substance (Plato's "fiery force") is created in the brain, gets out of the brain through the two eyes, swiftly reaches an object and learns and retains its shape, then returns to the brain through our eyes so that we "see" what is in front of us. A mirror, whose surface is smooth, bounces back the fiery force, which on returning to us picks up our image on its way and allows us to see our reflection.

Still, his works were copied and distributed, and influenced much of what was to come. His assertion of reason over blind acceptance of classical authorities was an important milestone in scientific thought. Many of his ideas are seen again in the writings of Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, and Hugh of St. Victor. Once the printing press was perfected, Adelard's translation of Euclid became a standard text for a hundred years.

*One of the followers of this blog is part of a group trying to promote inquiry-based learning in young people. Visit Prove Your World to learn more.

Monday, January 28, 2013

The First Protestant

|

| Hole Roman Emperor Henry IV |

Rudolph (c.1025-1080) had caused trouble for Henry before. Henry had become king at the age of 6, and Rudolph took advantage of the situation and used coercion to marry Matilda, Henry's sister, and be made Duke of Swabia. He was also given administrative authority over Saxony. As Henry's brother-in-law, one might think Rudolph would be supportive, but that same family connection and the resulting position as duke made him a suitable candidate for replacing Henry years later, even though Matilda had died in 1060 and Rudolph had remarried.

The election took place in March 1077. On 25 May, the Archbishop of Mainz crowned Rudolph, who agreed to be subservient to the pope's wishes in the future. The citizens of Mainz were not supportive of this move, and in the ensuing revolt Rudolph had to flee to Saxony. Unfortunately, this cut him off from his forces and home in Swabia. Henry, still acting as king and still supported by many Germans, declared Swabia given to Frederick of Büren.

Rudolph had difficulty getting the men of Saxony to leave their homes and fight for him. But in the next few years, he made minor progress against the forces of Henry. Also, the pope excommunicated Henry again, on 7 March 1080. Things seemed to be lining up for Rudolph, but the Battle on the Elster River in October was a turning point: Rudolph sustained wounds from which he could not recover, and died the next day.

Henry then tackled the real opponent: Pope Gregory. He invaded Rome and forced Gregory out, replacing him with Pope Clement III. (Clement's appointment was, of course, irregular, and he is considered an antipope. He was pretty bad in his own right.) Rudolph's brief reign is considered that of an "anti king."

When the Protestant Reformation came, Henry IV was touted as the "first Protestant" due to his opposition to papal authority.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)